Theodore Solomons was, in 1884, the first to have the vision of a high-elevation trail, passable by stock, which followed the spine of the Sierra from Yosemite Valley to Kings Canyon. He was only 14. “The idea of a crest-parallel trail through the High Sierra came to me one day while herding my uncle’s cattle in an immense, unfenced alfalfa field near Fresno,” he wrote in the Sierra Club Bulletin in 1940.

After more than 50 years, Solomons’s idea became what we know today as the John Muir Trail, thanks to the efforts of people who explored the Sierra both before and after him. Between Yosemite Valley and Mt. Whitney, features on maps honor John Muir, Josiah Whitney, Theodore Solomons, Joseph Le Conte, Joseph N. Le Conte (“Little Joe”), William Brewer, Clarence King, James Gardiner, Bolton Brown, and Wilbur McClure—to name just a few. Each man helped in the exploration of the High Sierra and the subsequent creation of the John Muir Trail.

Of course, the exploration of the High Sierra began long before the arrival of Europeans. American Indians had used the major passes across the range for centuries, both to trade with tribes on the other side of the mountains and to reach high-elevation summer hunting grounds. Tuolumne Meadows and the northern half of the San Joaquin drainage have the most evidence of American Indian use. Farther south, American Indians did not generally travel along the Sierra but instead crossed over the easiest passes and then dropped to lower elevations.

The first government survey of the High Sierra was during the 1860s. State geologist Josiah Whitney was tasked with making an accurate and complete geological survey of the state. In 1864 he assembled an impressive team of scientists to spend a summer exploring the High Sierra. His staff included William Brewer, a botanist; Charles Hoffman, an engineer and topographer; Clarence King, a geologist; James Gardiner, a surveyor; and Dick Cotter, an assistant. The party was the first to see many of the sections of the Sierra through which the JMT would later pass: the headwaters of the Kern River, Bubbs Creek, and the country along the South Fork of the San Joaquin River. They also discovered that in the southern Sierra there were two parallel crests, the Great Western Divide and the Sierra Crest, and they determined that the Sierra Crest was more than 14,000 feet high.

The first government survey of the High Sierra was during the 1860s. State geologist Josiah Whitney was tasked with making an accurate and complete geological survey of the state. In 1864 he assembled an impressive team of scientists to spend a summer exploring the High Sierra. His staff included William Brewer, a botanist; Charles Hoffman, an engineer and topographer; Clarence King, a geologist; James Gardiner, a surveyor; and Dick Cotter, an assistant. The party was the first to see many of the sections of the Sierra through which the JMT would later pass: the headwaters of the Kern River, Bubbs Creek, and the country along the South Fork of the San Joaquin River. They also discovered that in the southern Sierra there were two parallel crests, the Great Western Divide and the Sierra Crest, and they determined that the Sierra Crest was more than 14,000 feet high.

To survey the landscape, Whitney’s team climbed prominent peaks, including Mt. Tyndall and Mt. Brewer. In 1864, King and Cotter made a daredevil crossing of the Great Western and the Kings-Kern Divides. King spent years obsessed with reaching the top of Mt. Whitney, and while he did finally make it up the 14,505-foot peak, he was not the first to summit. Unfortunately, this period of state-sponsored exploration was short-lived; frustrated by the team’s focus on exploration and science rather than the discovery of mineral resources, the state discontinued funding in 1865 and later dissolved the survey.

Soon thereafter, Sierra admirers began entering the High Sierra on recreational trips, first exploring the Yosemite high country and then moving southward. John Muir was one of the first people to head deep into the backcountry, ascending peaks and exploring the country, often on solo knapsack trips. However, he was a naturalist at heart, more interested in staring at the plants, animals, and rocks than in producing maps of his travels or scouting routes for future parties.

Among the handful of other people venturing into the rugged country during the 1890s and 1900s, three names stand out: Solomons, who first envisioned the JMT; “Little Joe” Le Conte, son of Joseph Le Conte; and Bolton Brown. Like Solomons, Le Conte was intent on finding a route, passable by stock, between Yosemite Valley and Kings Canyon, while Brown simply enjoyed long, exploratory mountaineering excursions.

Among the handful of other people venturing into the rugged country during the 1890s and 1900s, three names stand out: Solomons, who first envisioned the JMT; “Little Joe” Le Conte, son of Joseph Le Conte; and Bolton Brown. Like Solomons, Le Conte was intent on finding a route, passable by stock, between Yosemite Valley and Kings Canyon, while Brown simply enjoyed long, exploratory mountaineering excursions.

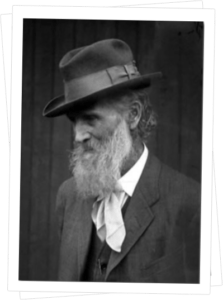

John Muir has become a folk hero as the father of the conservation movement. He was the first president of the Sierra Club, filling that role from its inception in 1893 until his death in 1914, and it is said today that more places in California are named in his honor than for any other person. He is even depicted on the California state quarter. However, his contributions to the Sierra were broader, as he published many scientific articles and was also an energetic hiker and mountaineer.

Born into a strict Scottish family in 1838, Muir’s admiration for the natural world began as a child. Disheartened by his early jobs in industry, he came to California at age 30, realizing that he wished to spend his life outdoors studying and simply appreciating nature. Following a brief visit the previous year, he arrived in Yosemite Valley in 1869 and spent his first summer as a sheepherder near Tuolumne Meadows. He was immediately entranced by the landscape, its vegetation and the geologic history, and disgusted by the damage caused by sheep.

Muir’s name became known for his theories on Sierra glaciation: he was the first to propose that many of the Sierra’s landforms, including Yosemite Valley, were created by glacial activity. Although he continued his scientific studies and long treks through the Sierra until his death, his focus soon shifted to the conservation of the mountain landscape. His talks, publications, and interactions with endless visitors to the valley established the concept of public lands and conservation in the national conscience. He realized that establishing national parks was the first step to preserving the land, but also that a legislative designation was only the beginning. Next he needed to assemble a group of supporters to help expound the importance of undisturbed wilderness to a wider audience.

The Sierra Club, founded in 1892, became his venue. It remains a powerful voice for both preservation of natural areas and the importance of people visiting these locations—for as Muir knew well, the public will only become vested in a national park’s worth as a place of national heritage if they experience the wonders for themselves. How fitting that the Sierra’s most famous trail and one of its largest wilderness areas are both tributes to him.

Eight years after his inspiration to build the trail, Solomons had saved the money and procured the free time to begin scouting this route. During the summers of 1892, 1894, and 1895, he took extensive trips into the High Sierra and mapped a route from Yosemite Valley south to Evolution Basin. However, he was unable to find a stock-passable route across the Goddard Divide. Instead, he climbed through boulder fields and bushwhacked, without stock, through the Ionian Basin and down to the Middle Fork of the Kings River. Little Joe Le Conte accompanied him for part of the 1892 expedition, and in 1896 Le Conte followed a path similar to Solomons’s from Yosemite to the Goddard Divide. There, he, too, failed to see today’s Muir Pass as a navigable route and instead led his party far to the west and into the North Fork of the Kings River.

Eight years after his inspiration to build the trail, Solomons had saved the money and procured the free time to begin scouting this route. During the summers of 1892, 1894, and 1895, he took extensive trips into the High Sierra and mapped a route from Yosemite Valley south to Evolution Basin. However, he was unable to find a stock-passable route across the Goddard Divide. Instead, he climbed through boulder fields and bushwhacked, without stock, through the Ionian Basin and down to the Middle Fork of the Kings River. Little Joe Le Conte accompanied him for part of the 1892 expedition, and in 1896 Le Conte followed a path similar to Solomons’s from Yosemite to the Goddard Divide. There, he, too, failed to see today’s Muir Pass as a navigable route and instead led his party far to the west and into the North Fork of the Kings River.

In contrast to the northern areas, the headwaters of the Kings River presented a barrier to crest-parallel travel for many years. It remained a challenge to find routes crossing the Kings–San Joaquin Divide, the Kings–Kern Divide, and the divides between the many forks of the Kings. Instead, parties accessed the region by traveling up the river drainages: the route from Cedar Grove to Bullfrog Lake and over Kearsarge Pass, and the route from Cedar Grove over Granite Pass and into the Middle Fork of the Kings River, were both stock-accessible and had already been traveled for many years by sheepherders.

It was by these routes that Bolton Brown entered the Sierra when he made long excursions into the South and Middle Forks of the Kings River (1895 and 1899) and the headwaters of the Kern (1896). Atypical for the period, he was often accompanied by his wife, Lucy, and, in 1899, also by their daughter, Eleanor. For JMT hikers, their most significant explorations included the discovery of Glen Pass (or Blue Flower Pass, as he named it) and the Rae Lakes region. However, he and Lucy were also the first people since the Brewer survey to cross the Kings–Kern Divide, and Brown extensively explored the headwaters of the South Fork Kings River and Woods Creek drainages, climbing peaks wherever he went.

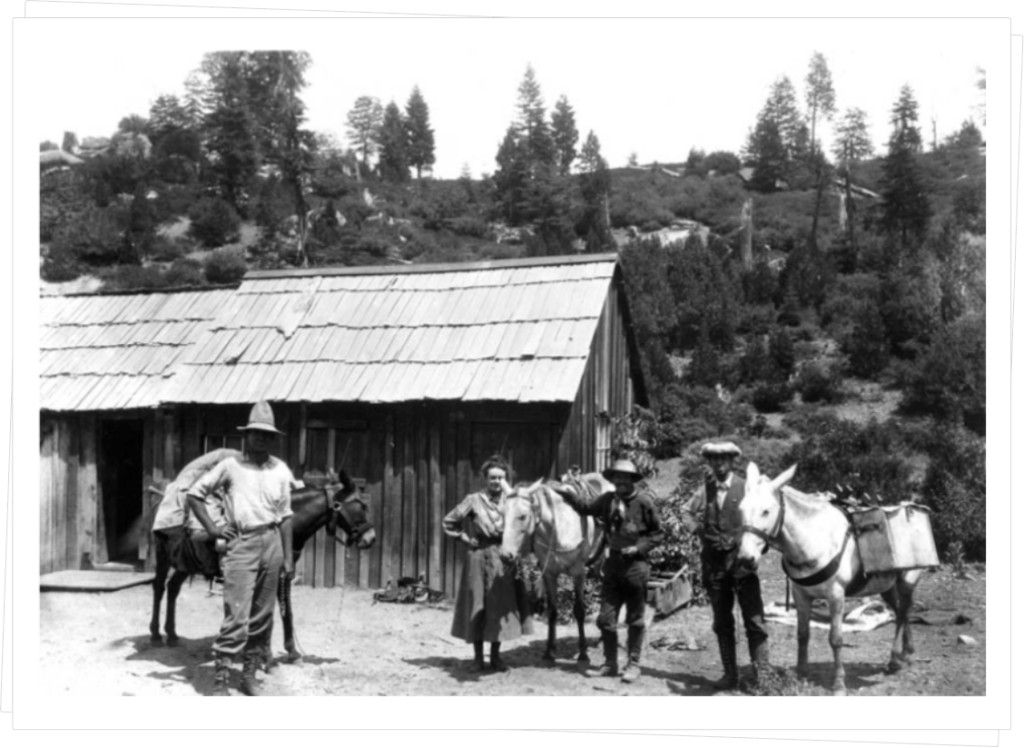

Joseph Nesbit LeConte, Duncan McDuffie and James Hutchinson, finishing the first JMT thru-hike, July 1908 (Photograph Courtesy of the William E. Colby Memorial Library).

It was Le Conte who finished piecing together most of a route through the headwaters of the King’s forks. During the early 1900s, he made numerous trips to scout for possible passes across which trails could be built, focusing his efforts on the Middle and South Forks of the Kings. In 1907 a U.S. Geological Survey party had succeeded in crossing the Goddard Divide (also known as the Kings–San Joaquin Divide) with stock, via the route that is now Muir Pass. A route across this divide had been the missing link in Le Conte’s route, and with this information, in 1908, he set out to travel from Yosemite to Kings Canyon. Excepting a detour up Cataract Creek (south of Palisade Creek), when their horses could not navigate what would come to be known as the Golden Staircase, the Le Conte party’s route was very similar to what would become the John Muir Trail as far as Vidette Meadow. Thereafter, he descended Bubbs Creek to Cedar Grove.

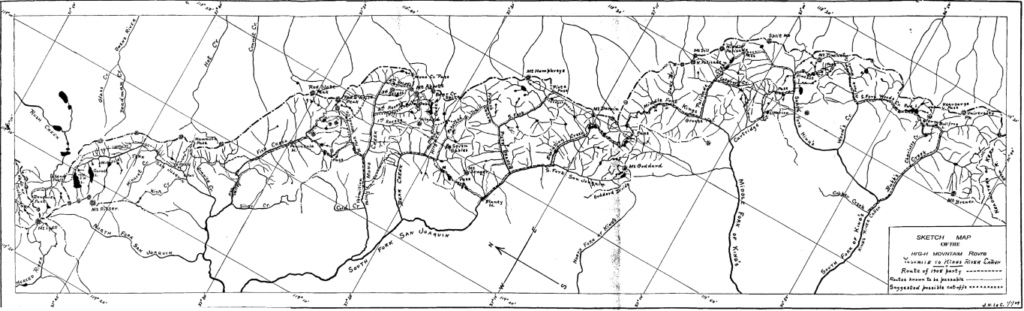

Hand-drawn map by Joseph Nesbit LeConte, Sierra Club Bulletin 1909, (Courtesy of Sierra Club William E. Colby Memorial Library)

As the headwaters of the Kern are less rugged, routes parallel to the Sierra Crest were easily found. Indeed, by 1908 the Kern River drainage was well-mapped, numerous parties had already climbed Mt. Whitney, and a rough use trail formed from Crabtree Meadow to Mt. Whitney’s summit.

Ever more people entered the High Sierra with stock during the next years, often as part of the large Sierra Club summer excursions that entered from the west and visited single basins. For despite Le Conte’s exploration, travel between the river basins was still difficult; Muir Pass, Mather Pass, and Forester Pass did not exist as navigable routes and most other passes sported only rough use trails.

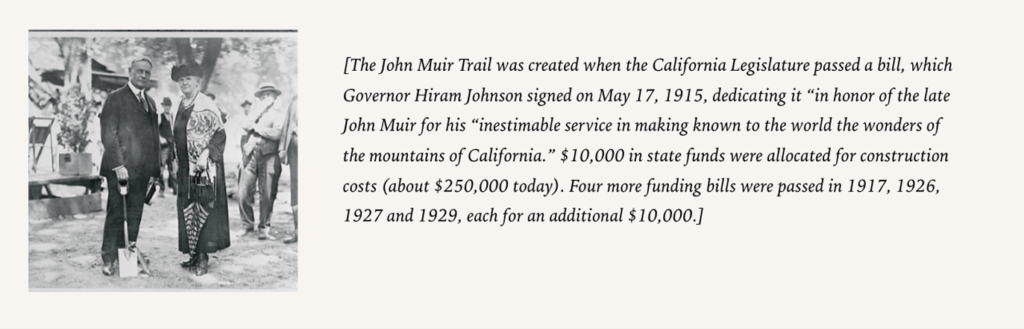

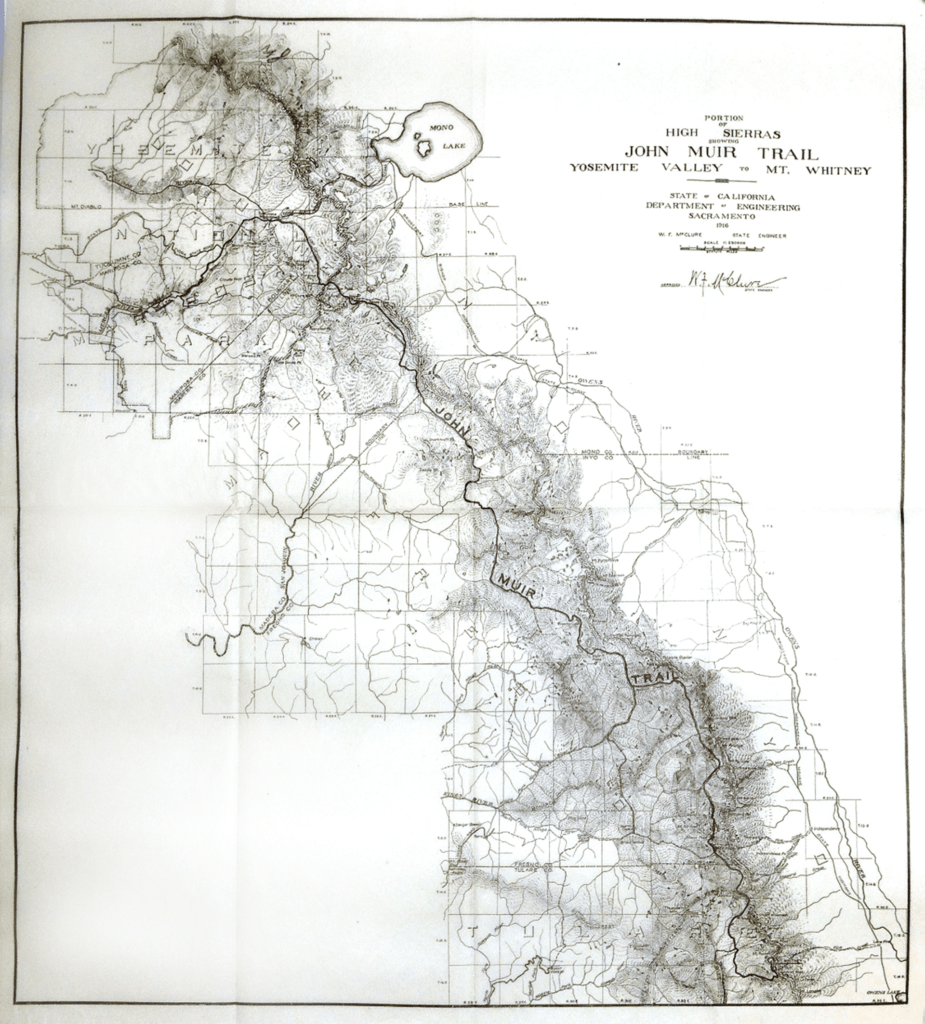

Only in 1914 did someone on an annual Sierra Club excursion suggests applying to the California legislature for funds to construct a high mountain trail to facilitate access to the mountains. The following year, limited funds were procured in Sacramento. The legislature gave Wilbur McClure, the state engineer, the task of selecting a route from Yosemite Valley to Mt. Whitney. From Yosemite Valley to Vidette Meadow, the route he selected follows, with remarkable fidelity, the route identified by Solomons and Le Conte. To the south, he initially selected a route through Center Basin, over Junction Pass to the east side of the crest, and back across the drainage divide at Shepherd Pass, as no navigable routes were known across the precipitous Kings–Kern Divide. Only late in the construction of the trail was Forester Pass “discovered” and the decision made to reroute the trail along this more direct route.

First official map of the JOHN MUIR TRAIL produced by California State Engineer W.F. McClure. (Fifth Biennial Report of the Department of Engineering of the State of California, Dec 1, 1914 to Nov 30, 1916 (1917). (Courtesy of Sierra Club William E. Colby Memorial Library)

Many of the explorers’ tales are written as articles in old Sierra Club Bulletins, other magazines, or in published journals, gaining them fame for their efforts. Less flashy, less recorded, but equally important are the efforts of the many men who built the trail. By the end of your walk, you will appreciate the effort expended to dynamite cliffs and build switchbacks through the never-ending talus fields encountered over most passes.

Impressively, a rough trail in two sections—from Yosemite to Grouse Meadow (Le Conte Canyon along the Middle Fork of the Kings River), and from Vidette Meadow (Bubbs Creek) to Mt. Whitney—was constructed within two years of funding. This included completely new stretches of trail over Muir Pass and Junction Pass. However, to bypass the areas that now host Golden Staircase, Mather Pass, and Pinchot Pass, hikers had to detour down the Middle Fork of the Kings to Simpson Meadow and then climb across Granite Pass to Cedar Grove, rejoining the current JMT route at Vidette Meadow. Once good sections of trail existed over Pinchot Pass and Glen Pass, one only had to detour down the Middle Fork of the Kings as far as Cartridge Creek and then climb across Cartridge Pass to reach the South Fork of the Kings below Taboose Pass.

Over the next many years, new stretches were built and rough sections were improved as funds became available. The trail to the summit of Mt. Whitney was completed in 1930, Forester Pass was finished in 1931 (only a year after the route was discovered), and the final section, the Golden Staircase, was completed in 1938.

Excerpts from: John Muir Trail: The Essential Guide to Hiking America’s Most Famous Trail by Elizabeth Wenk, Copyright © 2014 by Wilderness Press, pp. 96-105.